If I had a nickel for every time I heard Boone say that line, I’d have enough to go full-time on Jon Dowd’s Burner (note that we are a non-revenue generative operation). Boone isn’t the only one guilty; we hear this line all the time regardless of result. Huge offensive outburst? “Good at-bats.” Tough game with runners in scoring position? “Good at-bats.”

Baseball is a hugely results-oriented game, although with the rise of Baseball Savant, it has slowly swung the pendulum towards fans being aware of good process. Now that we have stats like Average Exit Velocity and Barrel Rate, we can cut through some of the results-based noise in baseball to determine whether or not a hitter is doing his job well.

Having a good at-bat (really, having a good plate appearance. But let’s keep the Boone bit going here) is hard to define and very much context dependent. Let me try and define what I believe to be a good at-bat. Obviously, a hit or a walk is a good result. Outs bad, baserunners good. For an out, that’s where it gets a bit complicated. Outs are valuable, since every team only gets 27 of them in a standard 9 inning game. On the flipside, the defense is working to get those 27 outs as efficiently as possible, including their pitching resources. Generally speaking, when a batter forces the pitcher to throw more pitches, it is incredibly valuable because it forces teams to churn through these pitching resources, pulling the starter early, and getting into the bullpen. The earlier and earlier you can force the opposing to team to consider goin to the pen, the better for the opposing team.

In a quality start, a starter has to go 6 innings and allow less than 3 runs. Let’s assume that the less than 3 runs condition is satisfied. So, a pitcher must record 18 outs in order to record a quality start. Assuming the MLB average WHIP of 1.3, that assumes that a pitcher has to complete about 4.3 plate appearances per inning (3 outs recorded plus the implied walks+hits). Over 6 innings, that would amount to ~26 plate appearances to cover. With a 100 pitch limit, that means a starter would have to maintain a pace of 3.88 pitches per plate appearance, which we round to 4.

So in isolation, if a batter is able to force a 4+ pitch at-bat, he is doing his part in starting the pitching change chain reaction. Let’s pressure test this with the the game log for the New York Mets at the New York Yankees 3-2 triumph on July 23, 2024, the game during which Boone made those comments: Jose Quintana faced 22 batters and threw 94 pitches, implying 4.3 pitches per batter. Based on my numbers, it looks like the Yankees did indeed have some good at-bats. Even while only giving up one run, Quintana was forced to leave after 5 innings, failing to qualify for a quality start.

So Boone was right, right?? Not entirely. The other part we have to look to is what the team is doing when they are able to get runners on base. Mets pitching during this game allowed 8 walks (4 of them to Aaron Judge, this will come back up later) and 5 hits, which is a fair amount of traffic to navigate around. Let’s take a look at what the Yankees did in some key situations:

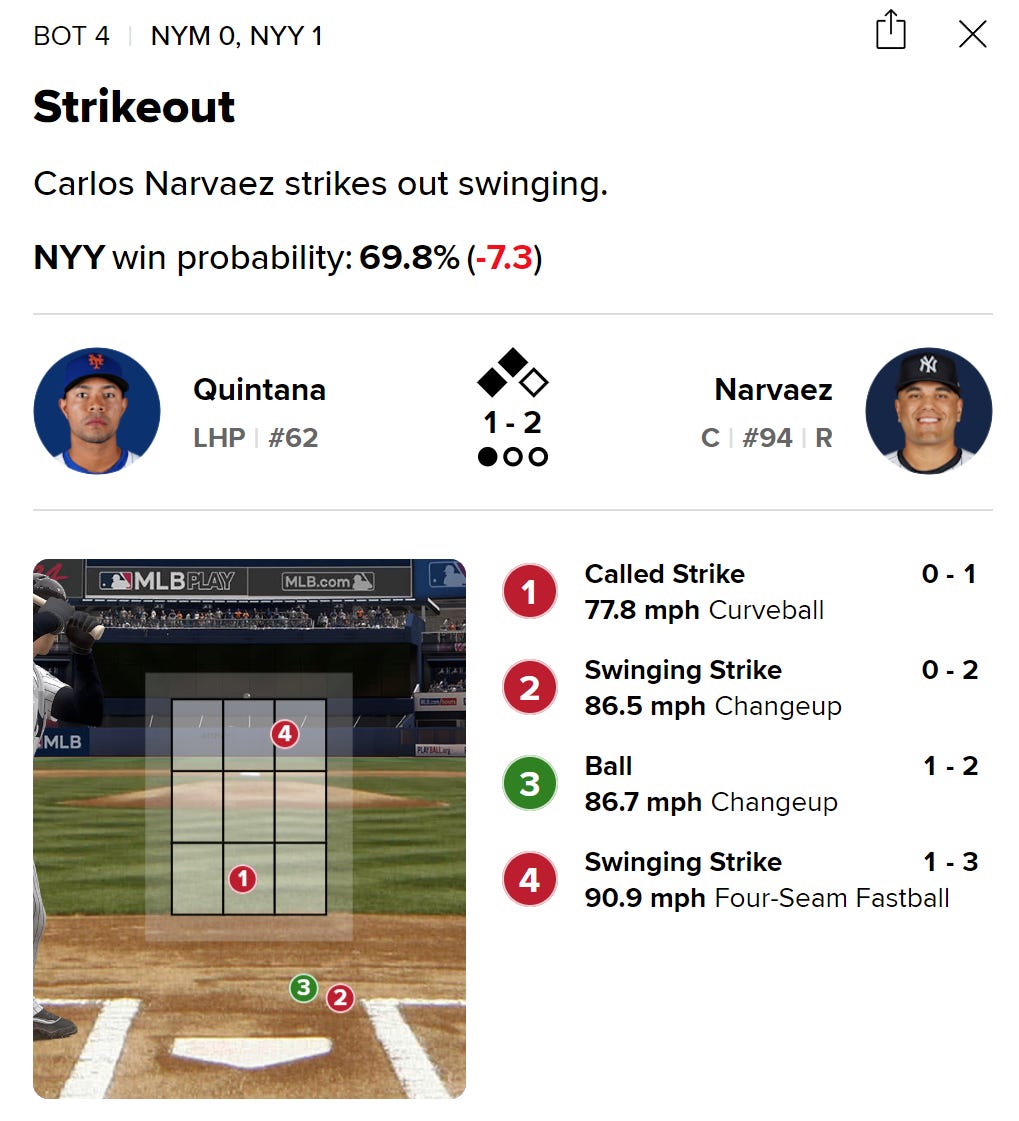

In the bottom of the 4th inning, Anthony Volpe and Gleyber Torres both reached based to start the inning. After an Alex Verdugo sacrifice bunt, the Yankees were primed up for the inning with runners on second and third with just one out. Up comes Carlos Narvaez:

In a situation where a fly out scores one and a single scores two, Narvaez strikes out on four pitches. Overall, a great pitch sequence by Quintana by first establishing two strikes, and then playing with verticality to get the swinging strike. Its a tough look when any contact gives you a fair chance to get a run. At least they have one more out to work with, let’s see who’s up next:

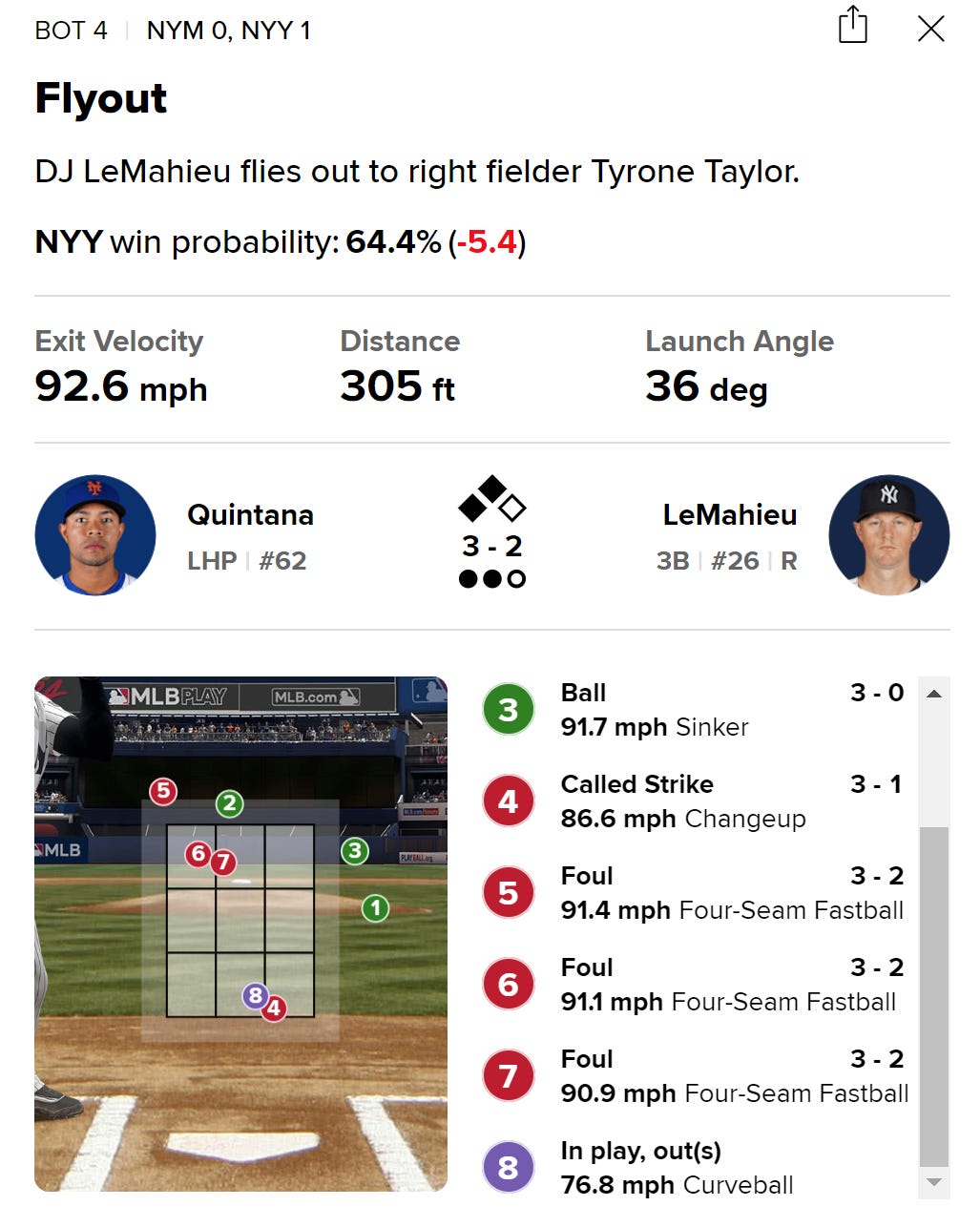

It’s not a stretch to say DJ LeMahieu is having a tough year. He works to an incredibly advantageous 3-0 count here. After taking a pitch, he swings at ball 4 to bring the count full. After a few foul balls, he flies out to right field. In a cruel twist of irony, if you had reversed the sequencing of the last two at-bats, the Yankees easily get a run on the board. A pretty terrible at-bat by Narvaez, followed up with a decent at-bat by LeMahieu, but not enough to get the job done.

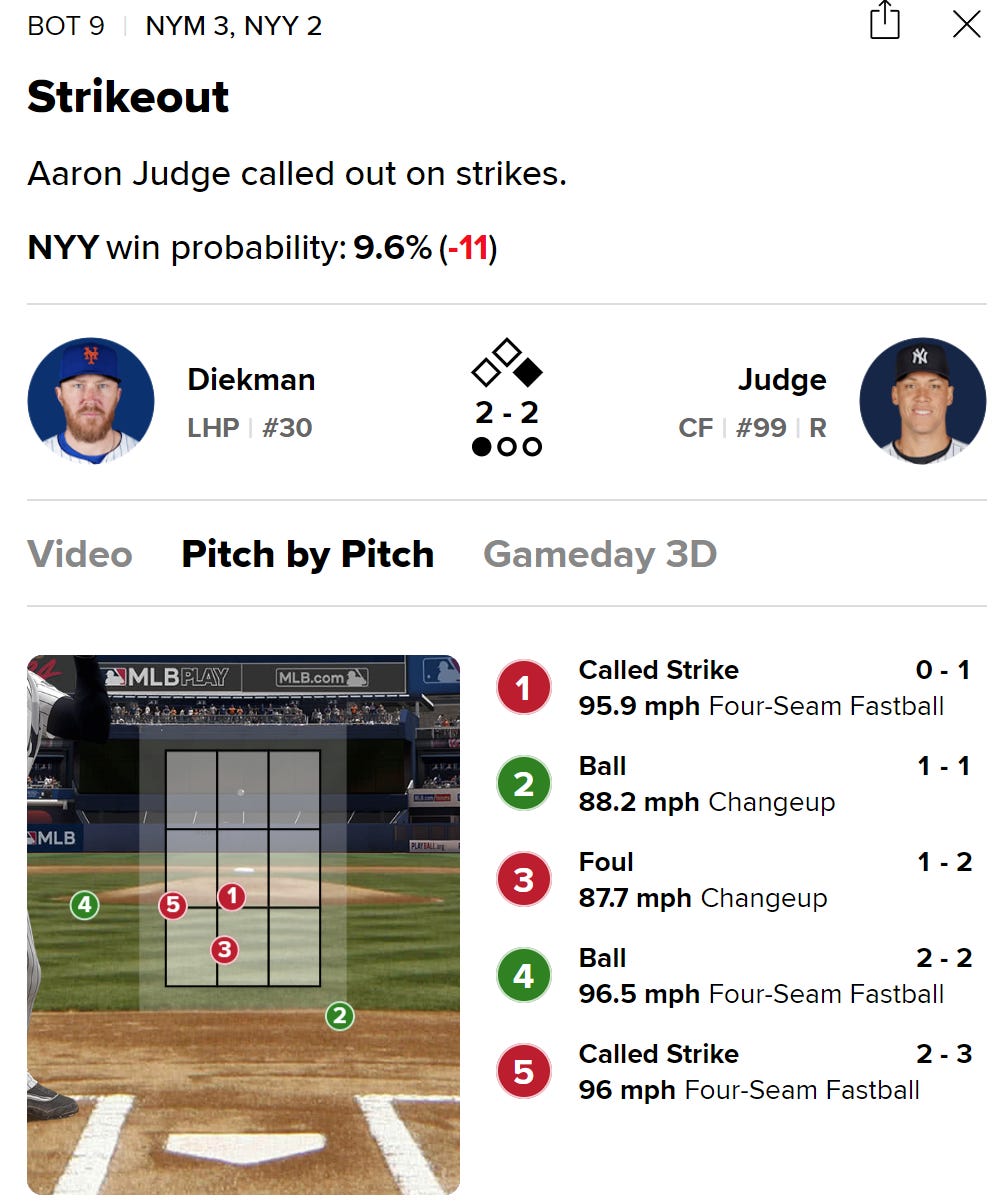

Finally, let’s look to the moment of the game that gave me heart palpitations. In the bottom of the ninth, with the Mets up 3-2, Jake Diekman(?!?!) enters the game to try and notch the save. After forcing a Trent Grisham flyout, he walks Soto (classic) to bring up Aaron Judge in a chance to walk it off with one swing of the bat. To this point, it was pretty obvious that the Mets’ gameplan for Judge was to completely pitch around him. Judge saw 18 pitches from Mets pitching, and none of them were particularly close. Enter the Jake Diekman experience:

Yes, that first pitch is right in the wheelhouse. But after seeing dog water for the first 8 innings, I think it’s totally fair to take that pitch. Judge then lays off a tough changeup, and proceeds to foul another one off with a lot of plate to make it 1-2. Pitch 4 is a beautiful brush-back pitch by Diekman, and he sets himself up for the killshot on pitch 5, with some inside paint. At that point, the momentum was so far on the Mets’ side that even with an out to play with, it was clear the Yankees were not going to get the job done.

Even though Boone is defending his team, there is some truth to his assertion that the at-bats were good. They successfully pushed Quintana out of the game by the 6th inning. They had plenty of traffic on the basepaths. But during the at-bats that mattered most, they were not able to push across the result needed to win the game.

If you made it this far, considering subscribing both to our podcast and the Skipper’s View page below:

-KL